#21: Can Journalism or Art Best Document China’s Climate Emergency?

A former award-winning photojournalist reflects on her experience covering extreme weather’s impact while navigating censorship and budget cuts in China.

In this week’s newsletter, I’ve invited Faye Liang, a photojournalist-turned-visual-artist, to write a personal essay on her evolving approach to covering the climate crisis. Faye reflects on her seven years as a photojournalist for one of China’s leading independent media outlets, during which she often covered extreme weather events. She also explains why she left journalism to pursue artistic expression while continuing to engage with climate change and social justice.

In this heartfelt essay, Faye highlights the challenges of reporting on climate in China. While extreme disasters are becoming more frequent, newsrooms are struggling with understaffing, underfunding, and constant censorship pressure. Journalists often fight for access to disaster sites, only to find that, once they get it, the frontline of the catastrophic weather event has already moved. Even when they manage to file reports, their stories may go “404” at any time, while readers, fatigued by repetitive “negative energy,” are losing interest. This creates a vicious cycle: vital information fails to reach vulnerable communities in climate-sensitive areas, leaving them uninformed, unprepared, and unable to build resilience.

Faye describes covering China’s climate crisis as “a Sisyphean task.” Anyone who practiced journalism in China would share this sentiment, caught between censorship, financial strain in the news industry, and reader disengagement, relying only on willpower and idealism – a “Quixotic act” – to continue their work.

In this constant tug-of-war, burnout is almost inevitable. It’s unsurprising that many in the industry face severe mental health crises. Ten years ago, when I worked as a journalist in China, nearly half the reporters in my news department suffered from depression, anxiety, or bipolar disorder. One colleague, hospitalized with severe depression, turned to public education on mental health but eventually took his life just before the zero-COVID policy was lifted.

Frontline reporters covering disasters and crises like climate change urgently need systemic support. When I covered the record-breaking rainfall in Beijing in 2012, there were no protections, emergency plans, or mental health support – even when our scoop exposed how “low-end” workers living beneath manhole covers suffocated to death, how a middle-class man drowned when his car got stuck in a flooded underpass in central Beijing, and how flash floods swept away dozens in their sleep who were never acknowledged in official records.

Unfortunately, the situation has not improved much – if anything, it has only deteriorated. Discussions on Chinese journalism still revolve around the same buzzwords: “censorship,” “propaganda,” and the operational challenges media organizations face. The well-being of individual reporters, these issues’ collateral damage, is rarely addressed. Meanwhile, many in the climate community tend to see journalists and media outlets as mere vehicles for their strategic messaging. Independent initiatives like Shuang Tan continue to struggle while sustaining our important and impactful work.

Curating and editing Faye’s essay over the past two months has been a painful and triggering experience for me – and undoubtedly for Faye. At one point, we had to pause the editing process and considered abandoning the piece altogether. Like many of my peers, I, too, went through years of therapy before I could finally see my experience as an investigative journalist in China as an asset instead of the source of persistent disappointment, despair, and defeat.

I hope you enjoy this newsletter. Share your thoughts in the comments. If you’d like to write for Shuang Tan, republish our articles, or submit a testimonial, email us at contact@shuangtan.me.

Until next week,

Hongqiao

Here at Shuang Tan, we write for impact.

We believe that to avoid the devastating consequences of runaway climate change, China must decarbonize, and decarbonize fast; understanding the country’s decarbonization drive is the foundation for any form of engagement to accelerate climate action in China and with China.

That’s why we’ve chosen the more challenging path. Instead of merely compiling news or exploiting the information asymmetry between the Chinese and English-speaking worlds, we are committed to providing unique perspectives, fostering meaningful dialogues, and building consensus on China and climate – arguably two of the most important, complex, yet least understood issues of our time.

Essay: Can Journalism or Art Best Document China’s Climate Emergency?

A former award-winning photojournalist reflects on her experience covering extreme weather’s impact while navigating censorship and budget cuts.

by Faye Liang

In June 2022, after heavy rain had flooded Qingyuan, in Guangdong province, a local farmer showed me around his submerged land on a rubber dinghy. The smell of dead pigs penetrated my nostrils as their inflated bodies drifted alongside the boat. Ducks, the farm’s only survivors, had found refuge on top of a shed. I saw a mouse paddle through the water as fast as its little limbs would allow. Just as the farmer, and perhaps all of us, it had no idea where it could find safety.

More than 3,300 local farmers filed insurance claims worth some 329 million yuan. Others, who couldn’t or wouldn’t pay for insurance, could only count on next year’s earnings.

It was one of many climate disasters I’d documented over the past seven years while working as a photojournalist in China. I believed that my work had purpose – most of all, that it could help the public prepare for future extreme weather. Every reporting trip taught me something new, until they became so repetitive that I started to doubt what I was doing.

In 2016, while covering a temporary settlement site for people affected by flooding of the Yangtze River, I first realized how climate change exacerbates China’s existing social issues. In a small village near Wuhan, evacuees – mostly seniors told to leave their homes overnight – shared with me their biggest concern was losing their livestock and crops, which they depended on to bolster their meager pensions.

Four years later, while covering another extreme rainfall event in a small town near Poyang Lake whose reservoir had overflowed, I learned just how resilient people can be. Despite a lack of experience and equipment, the local community displayed remarkable ingenuity. They crafted rafts from plastic buckets and wooden planks torn from submerged houses. These improvised vessels became lifelines, enabling them to transport essential supplies like food, clean water, and fuel.

I saw how extreme weather can take everything from someone – and then do it again. During a severe flood in Guangdong, in 2022, I met rural entrepreneur Mr. Huang. He had lost almost all his property overnight – floodwaters had drowned 80,000 pigeons in their tiny cages. Despite suffering a loss of 3 million yuan ($420,000), Huang was determined to rebuild his business. Sadly, this summer, his farm flooded once again.

Witnessing so many climate-related disasters up-close has given me a firsthand understanding of climate change and its social impacts. But covering the same tragedies again and again made me question the meaning of photojournalism. Was I truly making a difference?

A cloud of guilt enveloped me. My reporting hardly brought the changes that survivors hoped for, be that financial aid or environmental improvement; and sometimes, my coverage even seemed to worsen their situation. Though I now understand it’s not my fault, I still struggle to find peace with this cruel reality.

As global warming worsens, visual documentation of extreme weather disasters – with photos, videos, and illustrations – has only become more vital to make the public aware of and prepared for climate change. As Lu Guang’s award-winning work on environmental pollution and human suffering demonstrates, a well-crafted photo essay can have profound social impact, even in China.

However, high-quality photo reports have become scarce in China. Today, the country’s photojournalists face three major obstacles: the authorities’ tightening censorship, the public’s growing caution and distrust, and media companies’ diminishing willingness and ability to pay the high costs of covering extreme weather events.

My friend D, a veteran photojournalist, has spent the last six years documenting catastrophes across China. Increasingly, he feels overwhelmed: keeping pace with the growing frequency of extreme weather events has become a Sisyphean task. This April, after a historic town was devastated by floods and mudslides, it took him a week to secure approval from editors before he could start his difficult journey into the disaster zone. By the time he reached the scene, the extreme rainfall had already shifted north, causing floods elsewhere in other regions.

His photos also didn’t pass censorship. The public never saw them. Media were instead made to publish positive reports celebrating the triumph of disaster relief.

The increasing frequency of such challenges has intensified the sense of futility felt by many of my peers. We are often unsure whether our work will have any impact. Could my photo essays shift public perception of climate change? Would widely shared pictures of catastrophic scenes raise awareness and improve preparedness for future events? Might concerned citizens pressure authorities to implement more effective climate crisis mitigation and adaptation measures?

I firmly believe that climate coverage deserves more newsroom resources. We need not just photographers whose works can capture attention and evoke compassion, but also photo editors and curators who can place these works in the right contexts. As writer Mark Feldman has stated, environmental photography must be paired with facts and narratives to serve as an effective form of advocacy.

But in China, journalism might no longer be the best avenue for engaging the public on climate change. Last year, after being forced to leave a disaster scene once again, I left Caixin Media, a renowned Chinese media group, to explore artistic storytelling. Art offers more diverse creative and aesthetic expressions and facilitates public engagement. For instance, displaying climate images across various platforms, from fine art galleries to neighborhood billboards, can help reach new audiences.

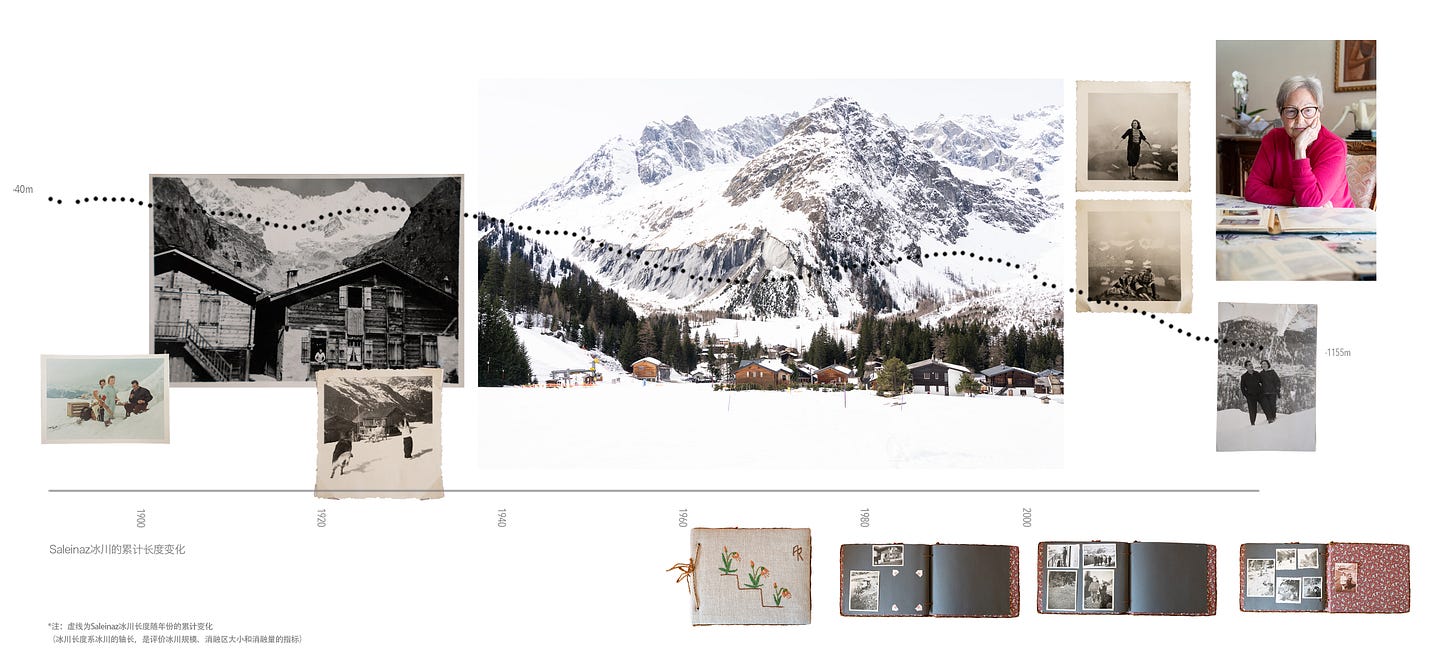

In 2023, I spent three months in Monthey, a small town in southern Switzerland, participating in an art residency that allowed me to create a series of works centered on glacial retreat. Twelve years earlier, it had been the photo exhibition “COAL + ICE,” a photo exhibition presenting the impacts of fossil fuels on glaciers and coal miners, that prompted me to become a photojournalist.

However, unlike its curators, Susan Meiselas and Jeroen de Vries, who transformed the project into an ongoing effort that documents experiences of vulnerable communities worldwide, I had very limited time – and resources – to present this urgent but relatively slow environmental process accelerated by climate change. Cultural and linguistic differences also challenged me to step out of my comfort zone to explore new perspectives in visual storytelling.

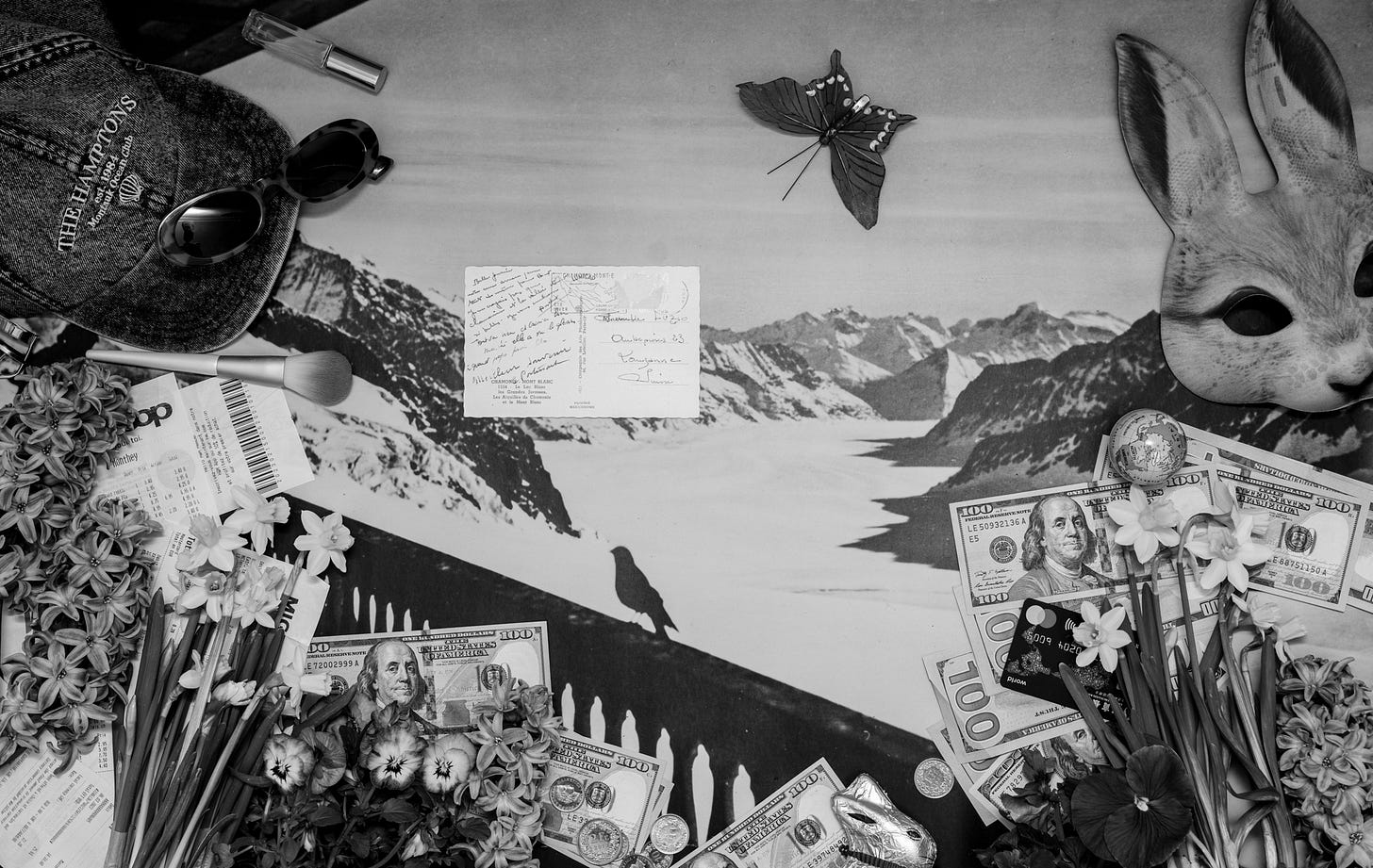

Inspired by Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung’s theories on myths and the collective unconscious, my multimedia works created a contemporary myth that depicts civilization’s vulnerability in facing climate change. I also combined scientific data, family photos, and landscape imagery to visualize the slow collapse of nature.

I was struck by Monthey’s vibrant cultural scene and the strong sense of awareness and activism on climate change among its residents. From young to old, numerous strangers have offered me resources and inspiration that I couldn’t have imagined accessing as a journalist in China. For instance, the local theater offered accommodation and exhibition space; a writers’ association organized a workshop that brought locals together to share their memories of glacial experiences; and mountain guides and residents generously contributed their memories, family albums, and concerns about the glaciers.

This project has unfolded as an open process, incorporating diverse narrations, archives, and second-hand materials from many individuals. It is also sustainable, as it can continue to grow by inviting more contributions from various communities. It’s the kind of art project that the restrictions of photojournalism would never allow: it has allowed me to shift the power of narrative from my camera to the hands of those directly experiencing the impact of climate change – a method I intend to carry forward in my future artistic explorations.

In China, many independent artists are also working on projects related to the environment and climate. Among them, the best known is perhaps Nut Brother, a performance artist who has curated series projects to draw public attention to environmental pollution and social issues. However, without a developing support system – such as art funds, exhibitions, and publications dedicated to environmental issues – it’s challenging to attract broader engagement. Nevertheless, my experiences in Monthey have inspired me to envision the potential of art projects focused on climate change, a topic that remains largely unexplored in China.

Support Shuang Tan

Shuang Tan is an independent initiative dedicated to tracking China’s energy transition and decarbonization. The newsletter is curated, written, and edited by Hongqiao Liu.

🎉 Shuang Tan has just become a partner of Covering Climate Now, a journalism collaboration project dedicated to improving the caliber and prominence of climate journalism.

🗞 We have also introduced a syndication offer for global news media outlets. China’s leading independent media group Caixin recently featured our coverage on its Chinese and English sites.

👀 In case you missed it: Please check out our new About and Testimonial pages and consider subscribing to ‘双碳精选’ for our best picks in Chinese.

💪 As a reader-supported publication, we rely on your help to grow. Each newsletter takes dozens of hours of dedicated work to transform complex, niche, and jargon-heavy essays into clear, balanced, and accessible articles. Upgrade your subscription to support us!

Get in touch

We will soon start accepting submissions. Stay tuned for our pitch guide!

For feedback, inquiries, and funding opportunities, please write to contact@shuangtan.me.